In our current choose-one, winner-take-all elections, each voter can choose one and only one of the available candidates on the ballot to fill one and only one electoral seat. In a two-candidate/one-seat election, this works very well. Suppose we have two political parties—Party A and Party B, and each party has one candidate in the race. In a choose-one, winner-take-all election, each voter would get to vote for one of the two candidates. If 60% of the voters vote for Party A's candidate and 40% of the voters vote for Party B's, then Party A's candidate would win. It's simple, it's fair, and it accurately reflects the will of the voters.

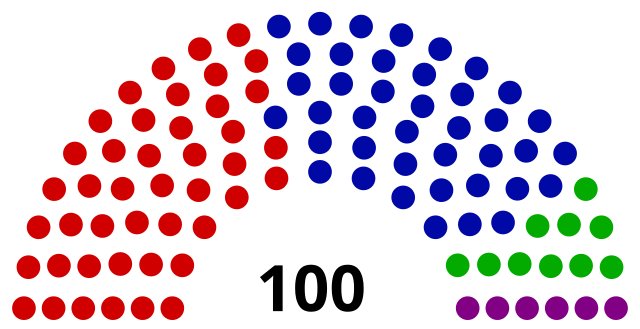

What happens when we introduce a third party—Party C—that has political views more aligned with Party A than Party B? Many of the voters who used to vote for Party A's candidate would be inclined to vote for Party C. Let's suppose that 60% of Party A voters still voted for the Party A candidate, but that 40% of Party A voters switched their vote to Party C. In this case, Party A's candidate would have 36% of the total vote (60% of 60%), Party B's would still have 40% (unchanged), and Party C would have 24% (40% of 60%). In a choose-one, winner-take-all election, Party B's candidate would be elected, even though fewer than half of the voters support the political views of this party. This is a problem known as vote-splitting, and it is the major flaw in the choose-one, winner-take-all approach to voting that is the current standard for elections in the United States of America.

Even though Party A and Party C have similar political views that collectively represent the majority of voters, the split votes lead to Party B's victory.

Ranked Choice Voting

One of the popular options to replace this system is Ranked Choice Voting (RCV). With RCV, each voter can vote for one or more candidates in the order of their preference. With regular RCV, the candidate who wins a majority of votes wins the election. If no candidate receives the majority, then the candidate with the least votes is eliminated and the second-choice candidate from each of the ballots cast for the eliminated candidate will be counted instead. This process continues until one candidate receives the majority of votes. While better than the current choose-one, winner-take-all system, RCV still has one major flaw: Popular second-choice (and beyond) candidates do not get equal representation. Consider the following sample election results in which Party A and Party C hold similar political views, and Party B holds political views that are unlike both Party A and Party C:

| Ranked-Choice Voting | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voter => | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 1st Choice | A | C | B | B | B | C | A | C | C | A | B |

| 2nd Choice | A | A | A | A | B | A | A | ||||

| 3rd Choice | B | C | C | B | C | B | C | ||||

Voter preferences:

9/11 (a super-majority) had Party A in 1st or 2nd place

5/11 (not a majority) had Party B in 1st or 2nd place

4/11 (not a majority) had Party C in 1st or 2nd place

6/11 (a majority) ranked Party A over Party B

4/11 (not a majority) ranked Party B over Party A

Traditional RCV would read the results as follows:

- Round 1:

3 votes for Party A, 4 votes for Party B, 4 votes for Party C. No one candidate won a majority. Party A had the fewest first-choice votes, so it is eliminated. The three voters who voted for it as their first choice have their second-choice counted. The six voters who voted for it as their second choice are not considered.

- Round 2:

4 votes for Party C, 5 votes for Party B. No one candidate won a majority. Party C had the fewest votes, so it is eliminated and the four voters who voted for it as their first choice have their second choice counted, unless their second choice was for Party C, which was already eliminated, in which case their third choice is counted.

- Round 3:

The eight remaining votes are counted for Party B, and it is declared the winner.

As you can see in this example, the majority of voters preferred Party A over Party B, but Party B was still the overall winner in the election.

For a more detailed analysis of the problems with RCV, watch the video below from Unify The Vote[1]:

The fundamental problem with RCV is that it leads voters to believe that their second-choice matters more than it actually does. The truth is the second choice (and beyond) only count if the first (or previous) choice candidate is eliminated. Until and unless your preferred candidate is eliminated, your ranking of other candidates is irrelevant. While this system may bring us closer to fair elections, it is easy to see that it does not effectively deliver on its promise to accurately represent the will of the people.

One District-One Representative

The problems with choose-one, winner-take-all and raw RCV are not only due to flaws with these systems. RCV may be an improvement over choose-one, but each has its advantages and disadvantages, and both are meant to solve the same problem: Ensuring that voters have fair representation in our government. There are other voting methods aimed at addressing this problem, such as Ranked Robin[2], Approval Voting[3], STAR Voting[4], and many others. The real problem is that most of these alternative voting methods still target winner-take-all elections where, regardless of the method used to determine the winner, there can only be one winner selected out of all the votes received.

If we want to fix our electoral system, we need to consider voting methodologies, but we also need to consider how many of the running candidates can be selected in each race. Prior to 1842, states were allowed to use bloc voting to elect multiple representatives from a single district. In this method, a single district might have three representatives. Voters could vote for three candidates out of however many were running, and the candidates with the most votes won. Just like in today's single-candidate races, the candidates from the majority party typically won most or all of the available seats, leaving the minority party with little or no representation in the district. By some estimates, one party could win about two-thirds of all congressional seats[5] by acquiring just over half of the overall votes.

This dilution of minority representation in Congress led to the Apportionment Act of 1842, in which Congress decreed that each district could elect only a single representative. This forced states to increase the number of districts within their states and appoint a single winner out of the candidates running in that district. While this move was intended to improve the representation of all parties in government, it was prone to gerrymandering[6].

This 1812 political cartoon depicts the shape of a political district outline in Massachusetts as a dragon-like creature. The practice became known as the Gerry-mander, after Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry and the word salamander, which at the time referred to a mythical dragon-like creature.

States are required to divide up their representatives into districts, and each district should have roughly the same number of constituents as every other district. This requirement was intended to make sure each district had equal political weight to every other district, but was prone to manipulation. States soon discovered ways to gerrymander the boundaries of each district to easily and predictably minimize or maximize the total number of representatives elected from a certain party in their state. This process drew significant national attention in July, 2025, when Donald Trump demanded five more Republican representatives from Texas, and state Republicans fell over themselves in their eagerness to curry their master's favor. Within weeks, they had redrawn the Texas congressional districts to ensure an additional 5 Republican representatives would win the 2026 midterm elections[7]. Gerrymandering is currently legal, as long as it is not done for racial reasons, which can be very hard, if not impossible, to prove in a court of law. This practice has been used to draw district borders for years, by all political parties, although some states have made attempts in recent years to hire non-partisan consultants to draw their district borders to avoid the appearance of voter suppression.

This image shows how gerrymandering can dramatically alter the political landscape. The first frame shows an area equally divided into 4 districts, with each district having an equal split between two parties and no way to predict how many representatives will actually be elected from each party. The second frame shows how the districts can be gerrymandered to guarantee that the same area with the same voter population will elect 3 representatives from Party 1 and only 1 representative from Party 2.

While single-representative districts were mandated to improve minority party representation in Congress, the practice of gerrymandering eliminates—or at least undermines—the benefits this system was supposed to deliver.

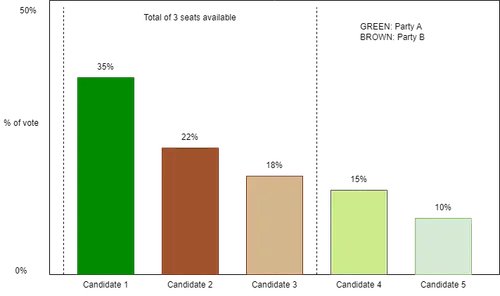

Proportional Representation

One possible solution would be to replace the Apportionment Act of 1842[5] and the Uniform Congressional Districting Act of 1967[8] with new legislation to return to the use of multi-representative districts, but to add a requirement that representatives within each district be apportioned based on the percentage of their support by voters[9]. This is called proportional representation, and it can be used to minimize the effects of gerrymandering by reducing the number of congressional districts in each state—fewer districts means fewer borders that can be adjusted to favor one party over another. This system would also give new parties a better chance at winning a seat because they would not need to win a majority of votes in a district, just enough votes to earn one of the available seats. And with more parties in the mix, it becomes harder to predict in advance who will win how many seats in each district, so gerrymandering will be less predictable (and thus, less useful) in this system.

The critical part of this system is to ensure that representation is proportional[10] to the parties represented. Without this requirement, we are right back into bloc voting from the 1800s that led to significant under-representation of certain parties. But how to apportion the votes proportionally is not always an easy thing.

Proportional Ranked Choice Voting

Even in multi-representative districts with proportional representation, you can run into situations where the actual preferences of the voters are not being accurately reflected. The most basic form of proportional representation ranks the candidates in descending order by the number of votes they received and fills the available seats from top to bottom until there are no seats remaining. The rest of the candidates are eliminated.

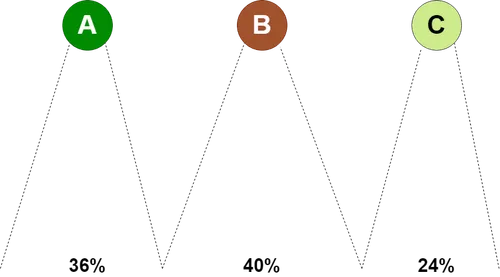

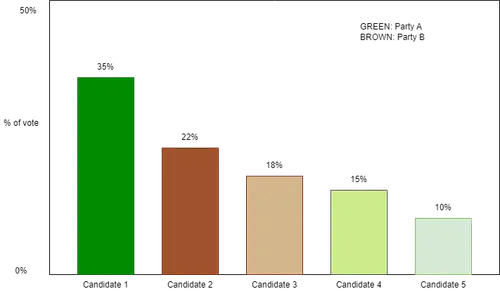

Candidates are ranked in descending order based on the percent of votes they received, and the top 3 candidates are given a seat.

In this example, Party A would get only 1 seat and Party B would get 2 seats, even though 60% of voters voted for a candidate from Party A as their first choice. This is a type of vote-splitting where Party A candidates were less likely to win a seat simply because there were more candidates representing that party for voters to choose from. This results in the over-representation of Party B and under-representation of Party A.

To address the shortcomings of this system, we can use Proportional Ranked Choice Voting to combine the benefits of proportional multi-representative districts with the benefits of ranked choice voting. Watch the video below for an overview of proportional ranked choice voting[11]:

The video glosses over some of the more detailed aspects of how the votes get counted, so I've expanded on these concepts below. This is a more complex process than the others we've discussed, so it will take a bit longer to explain.

Instead of just taking the top vote-earners from the pool of candidates until all seats have been filled, Proportional RCV allows voters' preferences for alternative candidates to be considered. It also ensures that more of those alternatives are considered than in traditional winner-take-all RCV. The first step is to determine the threshold that needs to be crossed to earn a seat. There are a few ways to calculate this, but the Droop quota[12] is commonly used to determine the minimum number of votes that a candidate needs in order to be awarded a seat.

Let's say we have 1,000 voters who are choosing between five candidates representing two political parties. There are three seats available, so to win a seat, a candidate must reach the threshold of 251 votes ((1000÷(3+1))+1).

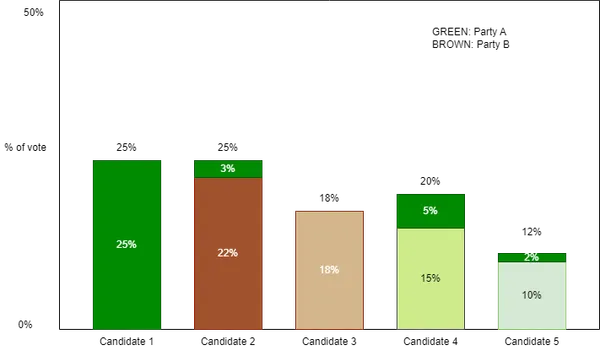

Round 1:

Round 2:

Candidate 2 was the second choice on 110 of those 350 ballots, giving Candidate 2 an extra 110 * 0.2829, or 31 votes (when rounded) to total 251 votes. None of the 350 ballots had Candidate 3 as their second choice, so Candidate 3 still has 180 votes. Candidate 4 was the second choice on 175 of the 350 ballots, giving Candidate 4 an extra 175 * 0.2829, or 50 votes (when rounded) to total 200 votes. Candidate 5 was the second choice on 69 of the 350 ballots, giving Candidate 5 an extra 69 * 0.2829, or 20 votes (when rounded) to total 120 votes. Six of the ballots did not have any candidate in second place. In this round, Candidate 2 has reached the threshold of 251 votes, and secures the second seat.

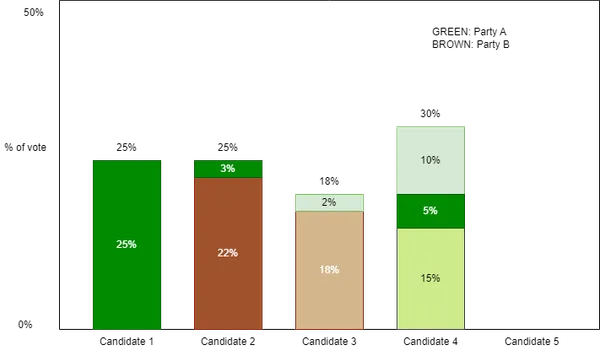

Round 3:

Let's see how we did: Party A ran 3 candidates and accumulated 60% of the total vote. Party B ran only 2 candidates and accumulated 40% of the total votes. When we used strict proportional representation, Party A won 1 seat and Party B won 2 seats, despite having fewer votes. When we apply Proportional RCV, we see that Party A ends up with 2 seats, while Party B gets only 1 seat. This is a better representation of the voter's expressed preferences.

In winner-take-all RCV, many of the voters never have their second-choice candidate considered. But with Proportional RCV, a voter's second-choice (and beyond) can be considered if their vote helps secure a seat for their previous-choice candidate and if their previous-choice candidate is eliminated. In the example above, the 18% of the voters who voted for Candidate 3 as their first-choice candidate did not have their second-choice (and beyond) considered. But the rest of the voters directly contributed to the selection of one or more winning representatives.

There is no way to perfectly represent voter preferences using a ballot because the number of candidates will always be limited and no candidate will perfectly represent all of the people who vote for them. But if we want our government to accurately represent the will of the people, we have an obligation to continuously evolve our electoral process to get as close as possible to representing the actual will of the voters. There is no reason why we have to keep running elections the way we do today, and there are plenty of reasons to make some changes. Those changes don't have to be permanent, either. As we see the results of the changes we make, we can make additional changes to continuously improve the process and ensure we always have a government of the people, by the people, and for the people.

Obstacles to Reform

Some changes are easier to make than others. Several states, counties, and cities across the country have already approved the use of Ranked Choice Voting in local, state, and/or federal elections, and their example can be followed by many others. But some states have written their election process into law, and it can't be changed without a state-wide constitutional amendment.

Changing the number of congressional districts and the number of representatives in each district can't be done without nation-wide congressional legislation that overturns the Uniform Congressional Districting Act and the Reapportionment Act of 1929[13] (Which replaced previous apportionment acts like the Apportionment Act of 1842 discussed earlier).

It won't be easy to build an electoral system that accurately reflects the will and the needs of its people, but it is part of the obligation all citizens have if they want to live in a representative democracy. We can't let the obstacles preventing immediate, radical, and nationwide reform stop us from changing what we can now. With each step towards a more representative government, we will find it becomes easier to perform the more difficult and larger-scale changes that we need to make in the future to truly perfect the system. Changing the way we run local elections can build the momentum needed to make more drastic changes to state-wide elections, which can build the momentum needed to make even more drastic changes to national elections.

References:

- (YouTube-Unify the Vote) Ranked Choice voting - The promise and reality

- (Equal Vote Coalition) Ranked Robin

- (Equal Vote Coalition) Approval Voting

- (Equal Vote Coalition) STAR Voting

- (Substack-Undercurrent Events) What the Apportionment Act of 1842 tells us about today's gerrymandering wars

- (Wikipedia) Gerrymandering

- (Politico) Texas GOP passes the House gerrymander Trump asked for

- (Wikipedia) Uniform Congressional District Act

- (Substack-Undercurrent Events) Democracy in pieces: Did the Texas gerrymander just break the districting game?

- (Wikipedia) Proportional representation

- (FairVote.org) Proportional representation

- (Wikipedia) Droop quota

- (Wikipedia) Reapportionment Act of 1929